Our Community

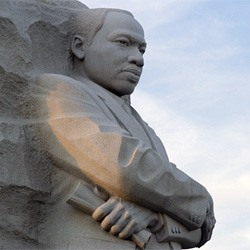

In this video blog, Tides CEO Melissa L. Bradley comments on the unveiling of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, reflecting on how King’s lessons can be applied to our current moment of wealth disparity and economic crisis. Watch now or jump to the transcript below:

Good day. This past weekend in DC, even through Hurricane Irene, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial was unveiled on the Mall.

Good day. This past weekend in DC, even through Hurricane Irene, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial was unveiled on the Mall.

The timeliness of this event should not be lost in the midst of all that is going on in the world and the US.

Now that the natural disasters are passed us, the country and media pundits return to our most pressing issue – the economy. The high unemployment rates, particularly amongst communities of color, are atrocious. Despite the stimulus, current repressed interest rates and the recession continue to widen the gap between the haves and have-nots.

The role of civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and many others must not be marginalized to just the pursuit of rights for people of color, but be raised up as reminders of the pursuit for the rights of the poor and the marginalized.

Throughout the civil rights movement, activists have always been engaged with economic issues, from using economic tactics like the Montgomery bus boycott and the boycotts of places like Woolworth’s that accompanied the lunch counter sit-ins, to economic demands, including the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his “I Have A Dream” speech was called the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. King began to focus more on economic issues in the last few years of his life. In 1966, he began working in Chicago and other major cities to address housing and employment discrimination, and in 1968 before he was killed, he was working on organizing the Poor People’s Campaign, bringing together poor people of all races in an attempt to win an “economic bill of rights” of anti-poverty policies.

In August 1967, the Rev. Dr. King spoke to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in a speech called Where Do We Go From Here? He said:

The problem indicates that our emphasis must be twofold: We must create full employment, or we must create incomes. People must be made consumers by one method or the other. Once they are placed in this position, we need to be concerned that the potential of the individual is not wasted. New forms of work that enhance the social good will have to be devised for those for whom traditional jobs are not available… Work of this sort could be enormously increased, and we are likely to find that the problem of housing, education, instead of preceding the elimination of poverty, will themselves be affected if poverty is first abolished. The poor, transformed into purchasers, will do a great deal on their own to alter housing decay.

He also noted, “We must honestly face the fact that the movement must address itself to the question of restructuring the whole of American society. There are forty million poor people here, and one day we must ask the question, “Why are there forty million poor people in America?” And when you begin to ask that question, you are raising a question about the economic system, about a broader distribution of wealth. When you ask that question, you begin to question the capitalistic economy. And I’m simply saying that more and more, we’ve got to begin to ask questions about the whole society.

On March 31, 1968, less than a week before he died in Memphis (where, by the way, he went to support the city’s garbage workers on strike), he spoke at the National Cathedral about the changes going on in the world, the challenges and opportunities they presented, and about the Poor People’s Campaign he was part of organizing. In a speech entitled Remaining Awake Through A Great Revolution, Dr. King noted:

There is another thing closely related to racism that I would like to mention as another challenge. We are challenged to rid our nation and the world of poverty. Like a monstrous octopus, poverty spreads its nagging, prehensile tentacles into hamlets and villages all over our world. Two-thirds of the people of the world go to bed hungry tonight. They are ill-housed; they are ill-nourished; they are shabbily clad. I’ve seen it in Latin America; I’ve seen it in Africa; I’ve seen this poverty in Asia…

Not only do we see poverty abroad, I would remind you that in our own nation there are about forty million people who are poverty-stricken. I have seen them here and there. I have seen them in the ghettos of the North; I have seen them in the rural areas of the South; I have seen them in Appalachia. I have just been in the process of touring many areas of our country and I must confess that in some situations I have literally found myself crying…

This is America’s opportunity to help bridge the gulf between the haves and the have-nots. The question is whether America will do it. There is nothing new about poverty. What is new is that we now have the techniques and the resources to get rid of poverty. The real question is whether we will have the will.

In a few weeks some of us are coming to Washington to see if the will is still alive or if it is alive in this nation. We are coming to Washington in a Poor People’s Campaign. Yes, we are going to bring the tired, the poor, the huddled masses. We are going to bring those who have known long years of hurt and neglect. We are going to bring those who have come to feel that life is a long and desolate corridor with no exit signs. We are going to bring children and adults and old people, people who have never seen a doctor or a dentist in their lives.

It is important that in order for us to know where we need to go, it is important to understand where we have come from.

The Center for American Progress did a wonderful historical on the progressive movement. They noted that at the turn of the 20th century, the nation as a whole began to experience unprecedented increases in prosperity with the advent of industrial capitalism, a rising class of wage earners, and shifts in agricultural production. But the many people left out of this growth and opportunity experienced widespread hardship. As a result, the search to build a more humane economic order—with decent living and work standards for all people—became the chief focus of a variety of progressive social movements in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The overall goal of these disparate movements was to increase the welfare of both workers and society at large and to create more cooperative forms of economic behavior that would replace the chaos of depression, class antagonism, and poverty that plagued the period.

Progressivism at its core is grounded in the idea of progress—moving beyond the status quo to more equal and just social conditions consistent with original American democratic principles such as freedom, equality, and the common good. Progressivism as an intellectual movement emerged between 1890 and 1920 as a response to the multitude of problems associated with the industrialization of the U.S. economy—these included frequent economic depressions, political corruption, rising poverty, low wages, poor working conditions, tenement living, child labor, lack of collective bargaining power, unsafe consumer products, and the misuse of natural resources.

The original Progressive Era is known primarily for two major developments in American politics:

These economic social movements drew on numerous sources including rising social justice sentiment in Christian and Jewish thought, a longing for the civic republican ideals of Jefferson and the Founding Fathers, rising labor solidarity, and new social science research in the fields of sociology and economics that explained the interdependence of individuals within society and the economy.

Unfortunately our challenges continue today.

The recent federal Budget Deal to raise the debt ceiling and the resulting fallout within the financial markets will undoubtedly have serious implications for our economic landscape. This ongoing economic uncertainty, now coupled with deep federal spending cuts, is likely to hit hardest those who are most vulnerable.

As philanthropic leaders committed to systemic social change, we are both uniquely affected by these decisions and have a special role to play. With even greater reductions in government funding and potential downturns in the financial markets affecting the ability of institutions and individuals to give, many non-profits will be expected to once again “do more with less.”

Tides is proud to partner with many of the leading voices in the social change sector to present a series that will engage our community, and the sector at-large, in critical discussion about how we can meet this economic and political challenge.

I ask that you join, support, and share this series. It is merely the beginning of an important conversation that started many years ago that Tides is honored and humbled to continue and lead.

I ask you to join us in the exploration of where do we go from here, and thank you in advance for your support and partnership.

Namaste.

Images adapted from photo by Flickr user Bsivad.

Read the stories and hear the voices of social change leaders fighting for justice.