LGBT

Last fall, Tides Director of Special Initiatives Roxana Shirkhoda joined a delegation of 50+ cross-sector advocates on a trip to Tijuana and San Diego on the United States-Mexico border. She captured her experiences in an original perspective piece, where she shares about what she learned and highlights six migrant groups to know about, including insights she learned from their experiences. This piece was originally published on Medium.

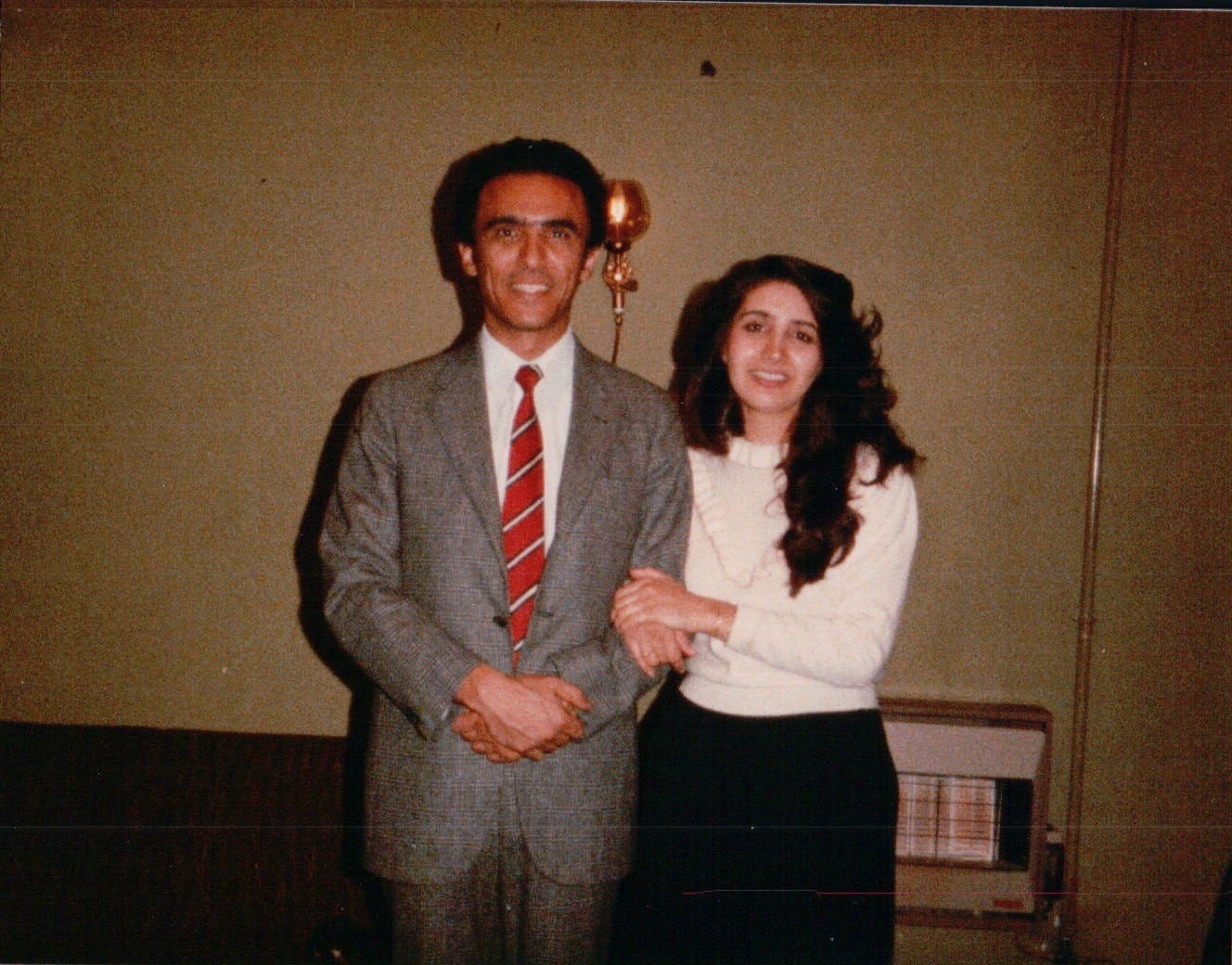

My parents separately migrated to the United States 41 years ago from Iran. Upon arrival to his residency program in New York, my father’s first boss asked him to change his name from Ali to Al. My mother, who came to attend college in Washington D.C., sat in class while young white men around her sang, “Bomb bomb bomb, bomb bomb Iraaan.”

I find it ironic that my parents, like millions of migrants today, fled their home to start a new life in the very country that helped instigate the challenging political climate that led to their departures in the first place. In a conversation about the Muslim Ban and the 20+ Iranian students recently denied re-entry to the U.S., my mother remarked, “I didn’t expect history to repeat itself in my lifetime.”

Ali & Shahrzad Shirkhoda, circa 1982.

The truth is, history never really stopped repeating itself. Immigration, especially in border regions, has continued to be a complex topic in the United States for decades with a recurring pattern of oppression, marginalization and othering of those whose existence challenges the status quo of white wealth, nationalism and power. To be clear, this nation’s DNA was coded in the 15th century by European migrants who stripped Native peoples of their sacred indigenous land, rights, and humanity. The same European migrants who created and spread the vile system of race based slavery and indentured servitude of Africans across the United States.

I have engaged in the immigration space as a champion for nonprofits led by migrants and people of color. My focus is on routing capital and capacity building resources to groups oftentimes flying under the philanthropy-radar, whose work is having a significant impact on either (or both) immediate service delivery needs, and long term policy change.

Last week I joined a delegation of 50+ cross-sector advocates on a trip to Tijuana and San Diego, a city with over 700k immigrants. As we stood on Mexican soil with the border wall towering over us, I wondered if it was coincidental or fortuitous the trip was planned on the 30th anniversary of the Berlin wall falling. History indeed continues to flatter itself.

Below are 6 migrant groups you should know about, including insights I learned from their experiences. I also share about deliberately induced trauma, and nonprofits you can support immediately.

Some facts are particularly challenging to square. Please note I share detailed and challenging examples below that migrant communities are facing. I also want to highlight the importance of not exploiting stories of migrants, but instead writing narratives that underscore migrant resilience and perseverance.

“If I don’t organize, I will die. My people will die.”

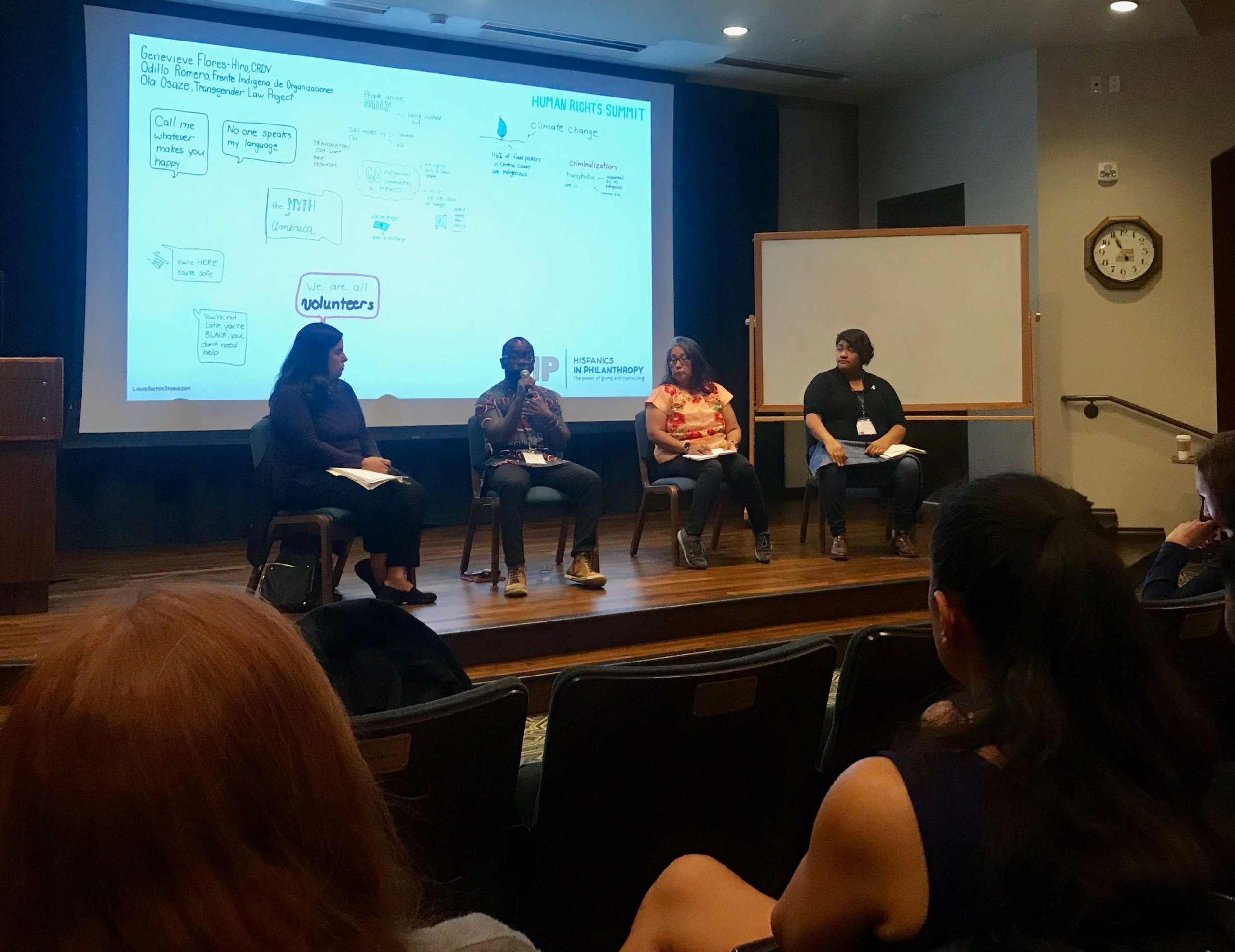

Speakers from California ChangeLawyers, Black LGBTQ+ Migrant Project, General Frente Indigena de Organizaciones Bionacionales, and Mixteco/Indigena Community Organizing Project.

69,500 children were detained by Customs & Border Patrol in 2019 alone, and 4,250 children have been separated from their parents since June 2017 and are still pending reunification.

Three factors (not exhaustive) leading to the plight of these groups:

Jardin de las Mariposas, Tijuana’s first rehab center and safe house for the LGBTQ migrant community.

One of the most dangerous tactics being deliberately deployed on migrants is the infliction of irreversible trauma.

Once they apply, migrants could wait several years before their case is seen before a judge — the uncertainty is often too much to bear.

Confusion, overwhelm, and fear are all tactics. From family separation to detention conditions; from ‘remain in Mexico’ to mass deportations; from DACA, to public charge, to census fear mongering — no one person can be expected to understand every nuance, or stay abreast of every policy change. This is all part of a deliberate strategy, more on that below.

Generational trauma is real; epigenetic research tells us that toxic stress is handed down from parents to children. While shelters provide individual and group therapy, the trauma can be so difficult to work through that some fall back into drug addiction to relieve the pain. One man described his experience migrating from Cuba — he traveled through 8 countries, saw over 50 people die trying to cross a river, and was stuck in a jungle for 2 days with no food. This man was a civil engineer in his home country, a judo black belt and when asked why he did all this, his answer was simple: “I just want a better life for my two children. I move forward for their future.”

To negate these tactics, we need to move money quickly to small groups led by people of color. Groups on the ground are repeatedly calling for more funding, more unrestricted funding, and more multi-year funding. We discussed the need for a holistic perspective on what is resourced — naming that we cannot lawyer or litigate our way out of the current situation, a bi-national and ecosystem approach is needed. Money has to flow to NGOs based in Mexico, we can no longer treat the border crisis as one-sided. Moreover, funders need to stop placing restrictions on what counts as impact, and lift the burdens of reporting so groups can focus on delivering said impact.

Jardin de las Mariposas, Tijuana’s first rehab center and safe house for the LGBTQ migrant community.

As we traveled out of Tijuana, it was not lost on me that we breezed through security check points to re-enter the U.S. My little 3.5×5 American passport was never questioned, just stamped and I was ushered forward. To know millions have come before me, walked those same exact steps, only to not succeed creates a dissonance that is difficult to reconcile. One local activist described a time they were trying to cross into the U.S and authorities began chasing their group of children. He said: “The minors that ran the fastest got into the U.S., and those that were slow were apprehended and kept in Mexico.”

I’d be lying if I didn’t admit I came home with a broken heart struggling to reconcile how hatred can claim so much power and do so much harm. But importantly I also came back inspired. Inspired deeply by those who are prevailing in the face of all odds (people of color have survived and thrived — standing on the shoulders of those who came before for centuries). I was also inspired by those who came together from many countries and areas of focus (government, law, organizing, philanthropy, asylum) to share together, learn from one another and commit to making progress with migrants around the world seeking a safe and just life.

The 6 groups I discussed are just the start. The demographics of our country are shifting (the U.S. is projected to become “minority white” by 2045, reaching a “minority majority” status in 2020 for those under 18), and our collective conscience continues to grapple with transitioning to a values-based economy from an exploitation-economy. Amongst it all, I have tremendous hope for a country that is inclusive, generous, and equitable.

I owe everything I have to my parents and their sacrifice in coming to this country alone four decades ago. It’s important to acknowledge that arriving here, and being able to stay here, is half the battle. While my parents navigated and ultimately were successful in securing citizenship, and together worked tirelessly to provide a nurturing home for me and my sister — growing up we experienced, and continue to face, challenges as a non-white immigrant family pushed to assimilate in America. Yet, we still prevail.

I leave you with words from Pastor Douglas: “Together we are more. United we are more.”

The views, information, or opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the individuals involved and do not necessarily represent those of Tides and its employees.

LGBT

Corporate Partners

Philanthropy

Read the stories and hear the voices of social change leaders fighting for justice.