LGBT

Rivers Without Borders (RWB), a project of Tides Center, is the result of a campaign initiated in the 1990s to challenge a large copper mine proposal targeting the pristine Alsek-Tatshenshini watershed region of British Columbia. RWB continues to work tirelessly to address ecological crises, including diminishing biodiversity, marine habitat degradation, and devastating impacts of climate change. RWB has been promoting and protecting the ecological and cultural values of the still largely pristine transboundary watersheds of southeast Alaska and northwest British Columbia, working with First Nations tribes, commercial fishermen, scientists, government agencies, community leaders, businesses, conservation advocates, legal and technical experts, media, and others to keep the transboundary region wild and thriving. We speak with Will Patric, executive director of RWB, on what the organization has been able to accomplish, what it’s focused on now—and why you should care.

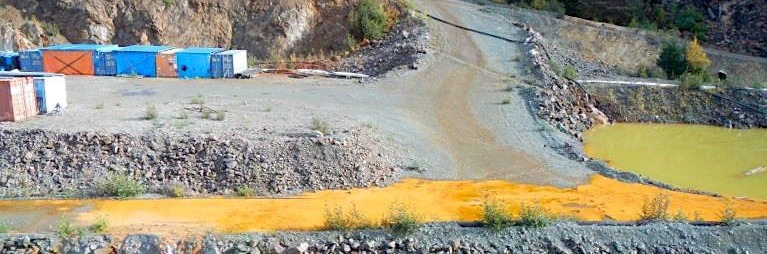

Massive mining proposals are targeting headwaters in the northwest British Columbia and southeast Alaska regions. RWB is not anti-mining, but they are pro-intact and thriving salmon ecosystems. (Photo of Tulsequah Chief Mine from 2016 BC Inspection Report)

How does Rivers Without Borders work at the intersection of environmental issues, equity, and human rights?

RWB raises awareness of the outstanding ecological and cultural values of the spectacular mountain-to-sea river systems shared by northwest British Columbia and southeast Alaska. We also promote visionary, ecosystem-based stewardship to sustain those values. Besides ranking among the top salmon producers on the planet, the Alsek, Chilkat, Taku, Whiting, Iskut-Stikine, and Unuk are remote, intact, and ecologically rich bastions of wildlife and biodiversity. Though mostly unprotected, the transboundary watersheds have been largely spared of development. But now the times have caught up with the region, and massive mining proposals are targeting headwaters. RWB is not anti-mining, but we are pro-intact and thriving salmon ecosystems. We believe that principles of conservation and sound watershed stewardship, with coordinated planning, meaningful stakeholder engagement, and visionary decision-making by governments on both sides of the border, should dictate the future of the transboundary region.

If not for RWB outreach, organizing, and networking, local interests would be easily ignored, with powerful mining proponents viewing the transboundary region headwaters as wide open to development. Among stakeholders, we believe indigenous voices should be preeminent, and we are proud to work with Tlingit communities on both sides of the border. For them, confronting proposed mining in their traditional territory, environmental and human rights concerns are one and the same. By engaging, organizing, and supporting many diverse watershed stakeholders, RWB is calling for their protection and amplifying the crucial watershed conservation indigenous voices.

How has climate change impacted the regions you work in?

Interconnected habitats provide a a resilient ecosystem that acts as a buffer to climate change. This biological refugia is critical in mitigating the impacts of a warming planet. (Photo © RWB)

The Alaska-British Columbia transboundary region has thus far been largely spared of significant environmental impacts relative to climate change. And there is a reason for this. With all native flora and fauna present and thriving, utilizing diverse and interconnected habitats over a large intact landscape, this robust and resilient ecosystem is a buffer to climate change. The wild transboundary watersheds make up what scientists call a biological refugia, this one recognized as among the most significant anywhere. Biological refugias won’t turn back the environmental crisis climate change poses, but they are a critical element of any hope of mitigating the most impacting aspects of a warming planet. And another reason why keeping the transboundary watersheds as they are now is so critical.

But here, too, salmon runs are impacted by global problems such as warming and more acidic ocean waters, as well as distant pollution. Overfishing can also be a factor, though we leave that issue to others, recognizing that without good spawning and rearing habits like that offered by transboundary rivers, there won’t be any fish stock to manage. At present, the bottom line for the Tlingit people of the Taku and Chilkat is that the salmon runs they depend on are not what they used to be, and maintaining the best possible watershed habitat is ever more imperative. Another big-picture environmental point is that in river systems to the south severely diminished by habitat loss due to dams and development, huge investments are being made in some of these watersheds to bring back a vestige of the ecological productivity that has been squandered. In contrast, in the transboundary region we still have a chance to get it right. No expenditures are needed. What’s required is appreciation, humility, and foresight acknowledging ecosystem values, along with a willingness to safeguard those values.

What is the main challenge you face right now, or your priority issue?

Current priorities are preventing new mine development in the Taku, getting an old abandoned and polluting mine in the same area closed and cleaned up, keeping mineral exploration in the Chilkat from becoming mining, and securing resources to sustain our efforts.

“Attention and pressure must be sustained to prevent the new mine, clean up the old one, and protect the region’s top salmon producing waters.” (Photo © RWB)

In the Taku—the heart of the transboundary region and the largest totally intact river system on the Pacific coast of North America—Rivers Without Borders and our indigenous and commercial fishing partners have been striving for years to stop an extremely controversial new mine proposal and clean and close a nearby polluting mine. There has been some progress, with RWB reporting that the British Columbia government, yielding to pressure, including from Alaska, has finally committed to ending the pollution. Attention and pressure must be sustained to prevent the new mine, clean up the old one, and protect the region’s top salmon producing waters.

To the north, intensive mineral exploration is ongoing in headwaters of the Chilkat river system. Just downstream is the Tlingit village of Klukwan. And just below that, the world’s only designated Bald Eagle preserve, with the Chilkat hosting the largest seasonal congregation of eagles anywhere. As with the Taku, the threat of mining likewise puts the Chilkat at a crossroads. Rivers Without Borders and our partners are confronting the exploration and calling for watershed protections now, before exploration becomes mining.

The biggest challenge at present is limited resources. Over the past decade, funding to support conservation work in our region has been trending downward at a time when more is needed. Now is the time to keep it up, as the transboundary region stands out as arguably the continent’s foremost conservation opportunity.

How can people help and/or get involved?

What we need most are dedicated watershed advocates, an established conservation constituency, and generous funding so we can do what we do. This said, we welcome volunteer interest and new ideas any time. Supportive letters about the importance of the transboundary watersheds to elected officials or media on both sides of the border are always helpful and appreciated. Of course, there are incredible storytelling opportunities with our campaigns to share the unique, natural beauty that is worth protecting and enjoying.

LGBT

Corporate Partners

Philanthropy

Read the stories and hear the voices of social change leaders fighting for justice.